Poor People is not a pleasant read. Indeed, it is a very difficult and challenging read, and I don't doubt that its author intended it that way. There is nothing I can say in critique (or in praise) of this book that hasn't already been said by writers more articulate and with more experience and clout than me. For me, it's enough to read the title and listen to myself as I say it aloud and hear everything implicit and subtly lurking behind that phrase: “poor people. Poor, poor people. Poor! People!” In those words I hear pity, fear and inevitable relief, that the speaker by default cannot be considered as one of the “poor,” since she/he can speak of them as something seperate and apart, something radically other and different from themselves. Disconnected. If you can view others as poor and thus by default radically separate from yourself, are you automatically saying that you by definition must be considered rich?

I read this book in between all the microfinance-related reading I've been doing over the past two weeks or so in preparation for my rapidly impending internship with Kiva (I'm getting on a bus to head to San Francisco for training tomorrow). I've read some pretty interesting stuff (especially the discussions about the commercialization of microfinance and the tension in MF about being focused on economic development or the marketplace, poverty vs. profit). Depressingly enough, I don't think microfinance would offer much in the way of a solution to the “poor people” profiled in this book. To be given a loan to start a business or purchase supplies or improve your house, it's already implied that you have already have started with something, as opposed to absolutely nothing. The people in these book really have nothing: they're the the sickly old beggar women, the smelly drunk and indigent, the crippled, the beggars in subway stations holding out palms or rattling plastic cups full of coins, the refugees, the fevered mothers holding their babies and staring down at the ground before them. God, this book is depressing.

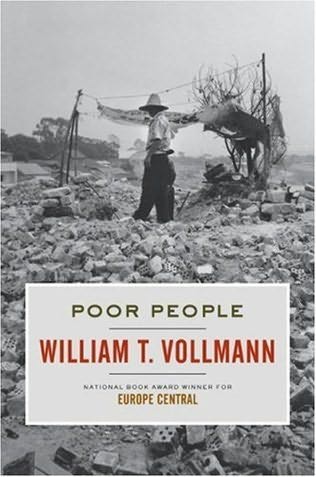

I did not particularly enjoy reading this book, which makes it hard for me to recommend it to people. I first stumbled upon it several years ago, in my stacks-shelving job at the college library. I flipped through the black and white portraits at the end and was intrigued by the number of photos that were of people from Colombia, and it's never really left my mind since. The images of beggar women in burqas in Afghanistan during Taliban rule are definitely remain the most affecting (Vollmann's discussion of poverty-as-invisibility ties in nicely to these images). The strongest bits of this book involve Vollmann-as-reporter, during which he simply profiles the folks he's interviewing. I liked the portrayal of the Russian family in which the husband was too sick from Chernobyl to work, and his foray into an off-limits oil refinery in Kazakhstan has the elements of a really angry documentary. He veers away from this simple reporting in the middle part of the book, instead going off on long tangents from his personal list of what defines poverty, such as “accident prone-ness” and “unwantedness.”

At one point in one of my flights and bus rides (it's hard to keep track of them lately!), I started doodling in my journal a list of WHY SHOULD WE FIGHT AGAINST POVERTY? The main reasons I came up with weren't so much academic as they were from my emotional gut. reason #1: Empathy: we're all born in this crazy ass world without really asking for it, and being that we're all in this sick mess together, we might as well help each other out... be a giver rather than a taker. Reason #2: Karma (in its most simplified definition): by helping others, you're helping yourself, and more importantly you're putting out a little positive energy out there into the black toilet hole of a universe for future use. Not exactly award-winning reasons, but for what it's worth that's what I succeeded in skimming off the top of my curdled-by-Greyhound brain.

I'm sure I'll have a lot more interesting things to say about poverty after I start Kiva internship, which I plan to blog about in more detail than I have so far in this space. In the meantime, one thing that really stood out for me in the wiki biography of Vollmann's life is how he dropped out of a Comparative Literature program at Berkeley “after one year with the intention of engaging life instead of just studying.” What an interesting phrase, “engaging life.” How does one go about doing that, pray? Is life something you just walk around and eventually find if you keep your mind open enough, or do you have to adopt a more proactive, aggressively-seeking approach?

For me at least, life as I've engaged it in the past week has been pretty pleasant, visiting my various girlfriends in Los Angeles and staying with my grandma in San Luis Obispo county. This evening my grandma and I looked at old photographs and I learned about Cosmo and Al, the guys my grandma “went with” before she met my grandfather. Poor Cosmo (a Navy fellow) was rejected on the account of insulting my great-grandfather's lawn, and Al (whom she “went with” for three years—long-term relationship, grandma!) went so far as to get her a ring, a fur coat and some kind of fancy box thing, all of which she rejected because “I didn't have feelings for him that way.” Poor Al.

(You can check out the non-profit(s) I'll be interning for until Christmas here and here.)

No comments:

Post a Comment