I went to Juarez spring break of 2005. I was a college freshman and the main preocupation of the trip was worrying about whether my Spanish would be accent-free enough to impress the Mexicans, and how much attention my ex-boyfriend (who also came along) would give me. Typical mindframe of the self-absorbed spoiled 19-year-old (I'm being hard on myself, but lah dee dah!). There are a couple of things I remember about the trip. I remember feeling completely terrified as we walked over the border from El Paso into Juarez; I was convinced that as a large group of white kids, we were going to be mugged immediately just walking down the streets (we weren't). I was impressed by how the people for the labor union we interviewed smoked inside their offices. One of them invited us to stay back at their house for the night and I remember being shocked that it was made of mud and tin--I guess I thought that since she wore nice clothes and worked in an office, the house would be nicer. It was very touching. I remember the anarchists whose house we slept in one night and how in awe I was of them. All in all, I think I was too young and inexperienced to absorb or analyze the experience properly. It was experiences like that that make me really believe in the validity of experiential learning: you really gotta get out of your self-absorbed head and experience education for yourself, first-hand. Your early experiences where you're kind of dumb and in over your head are like bricks that you're stacking for experiences later on in life, where hopefully your eyes and ears are a little more open.

In the same way that Che Guevara ate my May, Bolaño has completely swallowed my June. Maybe that's why this entire month has felt so weird and unbalanced to me: how can you expect to be in a sort of stable mind, when you're reading page after page of descriptions of horribly mutilated bodies of women found in the desert? Then you gotta put the book away, get off the Max and then hang out playing with kids for 6-8 hours. Talk about disjointed!

Unsurprisingly enough, there's a lot to be said about this almost 900-pg monster. I'm not even sure where to begin. I kind of feel the way I imagine I would feel after finishing "Ulysses" or "Moby Dick": simultaneously drained and exhilarated. I borrowed the book from a friend, so I couldn't underline any passages or fold the corners of the pages over when I read an excellent quote or a passage that felt particularly meaningful, so that makes me sad, because now, faced with the prospect of this "review", I have this 893-beast in front of me, and I have even less idea of where to begin than I would otherwise. So in advance, let me proclaim I am definitely going to have to re-read this, and thus analysis is definitely going to be very sketchy and first-impressiony, at best.

This book is very different from a lot of Bolaño I've read before--"epic" is definitely the first term that comes to mind. While other Bolaño books felt like the novels that Borges would have written (had he ever written one) "2666" is unmistakably and clearly Bolaño; there's no mistaking his style for another author's. What do I mean by Bolaño's style? I guess when I think of Bolaño, I thinkof the Murakami-like flourishes of what the characters ate or drank for dinner. The plotless plots where nothing really happens and nothing gets explained or resolved. His morbid gloomy view of life contrasted with the fierce joy his characters feel for reading and writing (a characteristic strongly reminiscent of Arlt's "El juguete rabioso" hero). That is Bolaño for me: witty, gloomy, harsh social realism, subtle political commentary, passionate crusader for the validity and worthiness of writing endeavors.

The book is divided into five parts, which all have titles like "The Part about the Crimes" (which unfortunately reminded me of the way "Friends" episodes are titled--the similarity ends there, thankfully!). The first book is the one most similar to the Bolaño I've read before: four literary critics, in the style of "The Savage Detectives", travel to the Mexican-U.S. border town of Santa Teresa (a fictionalized version of Juarez that easily deserves to be mentioned in the same breath of Macondo and Santa Maria) to track down an obscure German author, who may or may not have been last seen there. "I know the two of you will understand," is the last sentence in book one, but we don't.

Out of the five books, the fourth (the one documenting all the murders) is ironically both the most gripping and the most difficult to read. I feel sick about myself typing this, but it gets almost boring, turning the pages: oh, another murder, another death by strangulation, another unidentified decomposed body in the desert, another closed case, another police investigation that goes nowhere... I rached a point where I just felt numb reading name after name after name. The deaths quickly come to seem depressingly similar. Anally and vaginally raped. Body unclaimed and unidentified. Maquiladora worker. Eleven, twelve, thirteen, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, twenty, thirty-three years old. Bolaño isn't stupid, so this numbing effect is obviously what he was going for. What Bolaño does with thepolice detective genre is very intriguing, as he writes in this very matter-of-fact, CSI-documentation tone. The following quote is a pretty good example of most of the descriptions of the deaths:

In the middle of November the body of another dead woman was discovered in the Podesta ravine. She had multiple fractures of the skull, with loss of brain matter. Some marks on the body indicated that she had put up a struggle. She was found with her pants down around her knees, by which it was assumed that she'd been raped, although after a vaginal swab was taken this hypothesis was discarded. Five days later the dead woman was identified. She was Luisa Cardona Pardo, thirty-four, from the state of Sinaloa, where she had worked as a prostitute from the age of seventeen. She had been living in Santa Teresa for four years and she was employed at the EMSA maquiladora.

And so on and so forth in the longest chapter of the book. Anyway, so it's interesting that Bolaño uses this detective tone to describe this very physical, material evidence in the form of mutilated bodies, and yet despite all their materiality, this bodies embody absence more than anything else: there's no explanation for how they got there, no solution for the crime, and no resolution. Meaning is ecliped and absent despite this very matter-of-fact, supposedly transparent prose. Again: talk about disjointed.

This treatment of meaning (or as my blogspot tag puts it, "the form of truth") by Bolaño is something that definitely deserves a lot more thought (and not just because of his professed admiration for Borges, who loved writing his way out of stories without centres). For a lot of modernist authors (like Kafka and Conrad and so on), meaning was still around recently enough for them to still be pretty bummed about it draining away. That's why so much of modernist fiction seems to centered around the absence of meaning, something empty and silent and critical: hence the empty caves in E.M. Forster's India, Joseph K's crime, Virginia Woolf's lighthouse, Onetti's goat, Godot, Addie's monologue. There's definitely still traces of that critical silence and absence here in Bolaño. One of the questions I have is whether or not Bolaño he sees this absence of meaning as something to be all angsty and anguished about, or whether he sees literature and fiction as sufficent compensation for the disorder and meaninglessness of the world.

On that note, I think one of the most important things to mention when discussing what makes something "Bolaño-esque" is his use of absurdity. In the face of some things that could just never make any coherent sense (like why someone would shove a metal pole up at 12-year-old girl or bite a woman's nipple off and dump her body in the desert), sometimes absurdity is the best (and perhaps only) option. By absurdity, I mean all the extraneous details that go on for pages and pages: what characters dreamt last night, and all the random people who pop in for one scene of the novel and just as quickly pop out, never to be seen again (WTF is up with the psychic lady on TV? The Indian carpet-vendor girl one of the literary critics falls in love with? I could go on and on).

Another thing to consider when trying to define the Bolaño-esque is this quote by the one and only Eric Blair: "a novelist who simply disregards the major public events of the moment is generally either a footler or a plain idiot." With his use of Santa Teresaa as his stand-in setting for Juarez, Bolaño is definitely making very powerful political commentary about violence and power. I see violence as one of the main themes in this book: this dark beast that we have in all of us, which we need to get in touch with in healthy ways (a la Pip from American Doll Posse), but when we let it take control of us--yikes. Even the first book, the one about the literary critics, has this very interesting passage where they randomly beat the shit out of this Pakistani taxi driver. No one escapes, it seems, irregardless of your literary and academic pretentions.

The second book ("The Part About Amalfitano") is a character study of a university professor who may or may not be going crazy. It felt like the most random of the five parts to me. The image at the center of the second book involves a geometry book being hung out on a laundry line, slowly getting eroded by the elements as the professor waits to see how long it takes for the desert to destroy literature (this feels like a very important metaphor for the rest of the novel to me: how does literature stand up to the eroding, corrosive effects of the really harsh, fucked up reality that is our everday lives?).

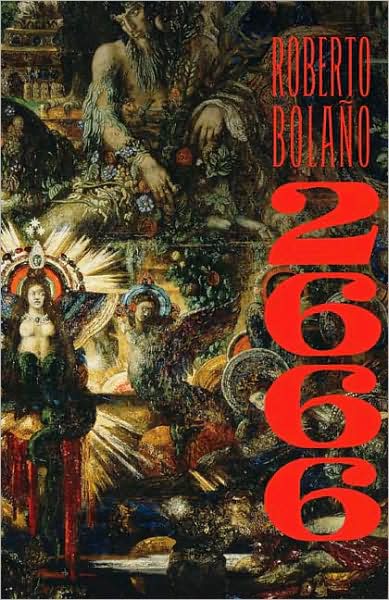

The fifth book is the the one about the German author, Archimboldi, whose name is apparently a homage to the the painter Archimboldo, whose work is depicted in the picture above--his paintings are of individual subjects that together form an apparent whole, just like how the five Parts in 2666 are meant to form one entire work. This book is the most surreal and dream-like. What to make of the last 3 pages? Why does this book end with a guy in a park talking about the different ice cream flavors his ancestor? Is it a commentary on the impermenance of art? The randomnee of life? A homage to Cesar Air and his fondness for strawberry ice cream in How I Became A Nun? Man, I don't know! Good God, give me a place in a PhD program and maybe I'll give it my darndest to figure it out!

"Apocalyptic" is another word that comes to mind for this book. When one of my co-workers saw the cover, he asked me if it was a book about the devil. "It doesn't seem to be yet," I answered honestly. I haven't even touched upon all the apocalyptic imagery and references to the Four Horsemen and the reoccurring images of the abyss and voids that keep coming up, again and again (as the review in Slate handily pointed out). Mental institutions and jails also appear in each of the five books, so I think that's probably important as well. There's also a lot of scenes that play with light and dark: on the last page, "Suddenly the park lights came on, as if someone had tossed a black blanket over parts of Hamburg." (893) Similarly, on the last page of Book 4 (The Part about the Crimes), "Some of these streets were completely dark, like black holes, and the laughter that came from who knows where was the only sign, the only beacon that kept residents and strangers from getting lost." (633)

For Bolaño, is literature the only beacon that keeps us from getting lost? Why else would the story of writers (university professors, academics, journalists, authors) be juxtaposed with the story of these crimes? Does Bolaño think fiction can save us, or is it a petty refuge, a distraction from the savageries of realism implemented by bourgeoise folks like the Jesuit priest in By By Night in Chile in order to distract us from the torture going on beneath the floorboards of our houses? In By Night in Chile and Distant Star, the violence always took place "off-screen." In contrast, the violence in 2666 is very front and center. I think that's why Germany plays an important role in the fifth and final book: if you want to write a book about torture and mass crimes and the apocalyptic end of eras, then yeah, WWII Germany is about as good of a setting as it gets. "The bones, the cross, the bones," is all one character can say in face of it all, and that's about as close to the the expression "the horror! the horror!" that Bolaño gets.

A lot of people are going to write their doctoral dissertations about this book in the next 5-10 years. This book makes me feel proud to be alive during the period in which it was written.

For further reading:

- A list of all the names of the women who have been murdered in Juarez, from 1993-2006, with a brief synopsis of death.

- Very good article from the Nation about 2666.

- The best article on Juarez I've read on the Internet, written for Salon by Max Blumenthal.

- Tori Amos' solo performance of her song "Juarez" from 1999--she looks like she's about to burst into tears at the end.

2 comments:

You should put ur blog on The Facebook and The Twitter so that more people can read it.

That's interesting about the Archimboldo painting... I was wondering what the painting is on the cover of my edition.

I liked the line from the Nation review where Bolaño is described as "crazier than a goat, you understand?" Something that interests me a lot about "Savage Detectives" and "2666" is this obsession with insanity. Probably if I write a blog post about "2666" it'll focus on The Part About Madness.

But considering you didn't take notes when reading I am impressed at the comprehensiveness of this post.

Yeah, I'd love to see your review of this!

I dunno if I'm ready to share this blog with the world just yet... maybe in a couple more months...

In the review I said that Part II felt the most random to me, but re-reading it I realized that I didn't say a word about Part III (the part about Fate), so maybe that ought to take the title... "random" is the wrong word though, when you take the time and effort to think about it, all the books tie in which each other in really interesting ways. God! Bolaño!

Post a Comment