The concern of the intellectual is by definition the conscience. An intellectual who fails to understand what is happening in his time and in his country is a walking contradiction, and those who understand but do nothing will have a place reserved in the anthology of tears but not in the living history of their land.--Rodolfo Walsh, Seminario CGT, May 1st 1968

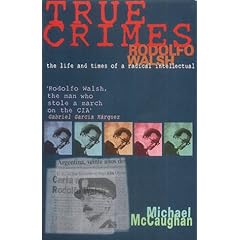

I've been reading a biography of Rodolfo Walsh (True Crimes: Rodolfo Walsh and the Role of the Intellectual in Latin American Politics by Michael McCaughan, Latin American Bureau 2000) which is also an anthology of his fiction and journalism translated into English. Not only has it been an interesting read, but it also has some eerily appropriate parallel themes with my current ponderings. Walsh was an Argentine writer and journalist, born of Irish ancestry and raised in a Catholic boarding school, wrote a In Cold Blood-like non-fiction work called Operacion Masacre, went to Cuba shortly after the Castro revolution in order to work in the news industry there and weirdly enough ended up intercepting a code from the CIA that gave away the location for the Bay of Pigs invasion, abandoned fiction to devote himself full-time to journalism and underground resistance work in the 70's once the political situation in Argentina really went down the drain, and was shot and killed in a shoot-out by the military in the middle of the street (his body was never recovered). He is counted as one of Argentina's 30,000 “disappeared” of that period. Isn't that weird, how you can sum someone's life up like that, in a couple of greatest-hits sentences? (I inevitably wonder what my own sentences will consist of...)

I haven't finished the book yet (I'm at the part where he gets really intensely involved in underground resistance), but there have definitely been some moments in the book that have given me pause and thus merit some reflection here. The short stories are excellent, particularly "Footnote" and "Esa mujer" (check them out). There's a lot of discussion in the book (as indicated by the subtitle) about Walsh's struggle with the role of the intellectual in society, which I found personally quite relevant... I feel uncomfortable about calling myself an “intellectual,” but I definitely read a lot, and like thinking about things that probably a lot of people would consider quite silly, such as “what is the role of the intellectual in society?” (After Barry-O's election and Georgie's reign, this question has been given a bit more attention.) I went to an expensive college, my parents are well-educated. I like reading fiction, writing fiction (goes without saying I need to do this one more), writing and talking about fiction. Yeah... I am pretty much a bourgeois intellectual.

I guess I struggle a lot with how relevant all of this is (the reading and writing and talking about fiction). I like doing a lot of other stuff to, outside of this—I like working with people, I like being with people, I like doing things that feel like they make more of a difference in a day-to-day sense. My job isn't super prestigious or super high paying or anything like that, but someone's got to hang out with these kids and give them something positive in their lives, you know? I dunno, I'll just say that I find it relevant and then leave it at that. My struggle (which I was reminded of again and again in this book) is finding a balance between these two things: the whole isolated hermetic ivory tower writer and intellectual tradition versus the nitty-gritty, down and dirty, involved in the world role. Is there a way to combine the two? Does it really come down to choosing one or the other? Is the role of books in my life destined to be restricted to a hobby, a sideline entertainment, or will it become a career? (The latter's up to me to decide, I guess.) Interestingly enough, in some of the interviews with family members and friends, a lot of them express frustration about Walsh's choice of journalism over politics... there's a certain attitude in their words of "oh, he could have been one of the greatest Argentinean fiction writers, he had so much potential, but then he went ahead and got involved in politics and justice." I don't think there's really a right or wrong choice; it's just a matter of the type of person you are... some of us are content, others of us are a little more scattered and need to explore different roles and careers in order to find that kind of satisfied fulfillment...

I folded over the upper-right corner on the page where Walsh is having a conversation with another young aspiring author, in his early 20's (this really hits home in terms of the theme of this blog):

“These are different times, Nicolas, and this is a time for a bigger undertaking. When you're trying to change important things, then you realize that a short story, a novel, aren't worth it and won't satisfy you. Beautiful bourgeois art! They taught us that it was the supreme spiritual value. But when you have people who gave their lives, and continue to, literature is no longer your loyal and sweet lover—it's a cheap whore. There are times when ... every spectator is a coward or a traitor. This might be a pain for the more intimate questions of the soul but that's the time we're living in.” (218)

You see this same question in a lot of Roberto Bolaño works. I just read La estrella distante (Distant Star), a 140-page novella that makes for a quick and thought-provoking one-day read. This book talks more about writers and poets than anything else, specifically one poet, Alberto Ruiz-Tagle, who gets involved with the Pinochet Regine by writing state-approved poetry in the sky. If you like Bolaño, you should definitely read this work. I never realized how influenced by Borges he was, either. I'm starting to see this as a common denominator in a lot of the stuff I've been reading or re-reading lately (Lolita, The Island of the Day Before). I don't want to give too much away about the book (part of its impact is being shocked by its unexpected development), but the novel deals with the same question discussed in the Walsh biography: what is the relationship between literature and real events? Is turning to literature when unimaginably violent events are taking place in your immediate world brave or just blind and stupid? The insightful New York Times book review of Bolaño's The Savage Detectives makes an important point:

What can it mean, he asks us and himself, in his dark, extraordinary, stinging novella "By Night in Chile," that the intellectual elite can write poetry, paint and discuss the finer points of avant-garde theater as the junta tortures people in basements? The word has no national loyalty, no fundamental political bent; it's a genie that can be summoned by any would-be master. Part of Bolaño's genius is to ask, via ironies so sharp you can cut your hands on his pages, if we perhaps find a too-easy comfort in art, if we use it as anesthetic, excuse and hide-out in a world that is very busy doing very real things to very real human beings. Is it courageous to read Plato during a military coup or is it something else?

Yeah... I'm just trying to figure stuff out, I guess. I am in a certain position of power and privilege, in the sense that I have choices of what to do with my life. And just like in Spiderman, "with great power comes great responsibility." So I am trying to figure what I want to do with my brain, and how I can find something to do with my brain that feels both worthwhile and valuable. So it goes.

.jpg)

Maybe getting glasses is the common denominator behind figuring everything out.

3 comments:

The question is, is Literature a cheap whore, or a cheap whore with gonorrhea?

& y'all stole my facebook quote for ur masthead. H8ter.

But in all seriousness, this quote reminds me of the George Orwell essay where he says all good literature must be politically motivated, and all his "bad" books are the ones that were written without an explicitly political purpose.

What's the name of the essay?

I need to read me some more Orwell, I do... have you read "Burmese Days"? If yes, what did you think of it?

I think it might be "Why I Write."

I really liked "Burmese Days" - I thought it was well written, and it didn't take an easy view of colonialism - no rah-rahing the British as baddies, pure & simple. He showed it was more complicated than that - colonialism creates these situations where local leaders are also corrupt and oppressive.

Post a Comment